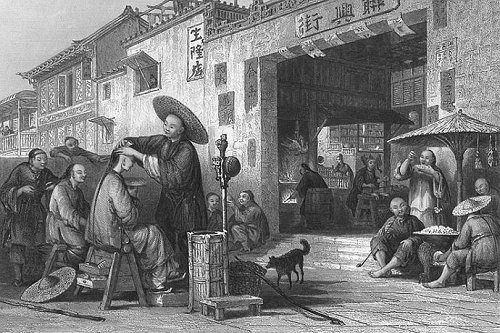

The ancient Chinese wore the hair long, a practice the aborigines of most countries are observed to follow, and only discontinued it upon compulsion. While they were permitted by their Tartar conquerors to retain their religion and laws, they were obliged, as a badge of servitude, to shave the head, with the exception of a single tuft upon the crown, that renders baldness visible. Time has softened the sentiments of sorrow that accompanied this humiliating mandate, and the adoption of the custom by all classes in the empire has at length obliterated the painful recollection of its origin. And now, the universality of the habit has created a necessity for a very numerous corps of barbers, who are all itinerant, and placed under very strict surveillance, a severe penalty being attached to practising the art without a regular license from the magistrates.

Not only the head but the whole of the face is to be passed under the razor, so that no Chinaman can perform this indispensable ceremony for himself, hence an additional necessity for an enlarged number of professional operators. In Canton, alone, upwards of 7,000 barbers are constantly perambulating the public streets, indicating their locus and their leisure by twirling a pair of long iron tweezers. Across the barber's shoulders lies a long bamboo lath, from one extremity of which is suspended a small chest of drawers, containing razors, brushes, and shampooing instruments, made of white copper. This piece of furniture serves as a seat for customers, and its counterpoise, which is hung from the other end of the shoulder-lath, consists of a water-vessel, basin, and charcoal- furnace, enclosed in a case. No beards being allowed to grow, no moustache permitted to remain before the age of forty, nor a single hair suffered to wander over any part of the face, the attendance of a barber is lastingly requisite, and considerable dexterity indispensable; and the adroitness which they display in shaving the head, eradicating straggling hairs, and giving a clean and spruce ensemble, is almost an object of curiosity. A Chinese razor is clumsy in appearance, but convenient in operation, and whenever the edge fails, it is restored by friction on an iron plate.

But, shaving is a less scientific part of a barber's vocation than shampooing, a custom practised in many eastern countries ; and the instruments provided for this extraordinary mode of quickening the circulation of the blood, are not only numerous but delicately formed. The candidate being seated on a large chair, the operator beats rapidly with both hands upon all parts of his body. The arms and legs are next stretched, and with sudden jerks that give the idea of dislocation. Sometimes the patient is pulled by one arm, his head being pushed in the opposite direction, the finger joints cracked, and the quick beating repeated, the operator at intervals philipping with his fingers. Instruments are now employed; the application of a brush, resembling the globular flower of the acacia, succeeds to that of the ear-spoon, a thin slip of horn, and lastly come the tweezers and the syringe. Nor does the extreme delicacy of the eye save it from the invasion of these professors of luxury. Several small instruments are applied to this tender organ, without injury, probably with advantage. The eye-pencil consists of a pellet of coral attached to a slip of horn; this is thrust under the eyelids, and turned about with rapidity, producing, of course, a copious flood of tears. Shampooing, the ceremony of which lasts half an hour, and for which a penny is the usual compensation, is closed by paring the nails of both toes and fingers. The Tartar proclamation prohibiting the wearing of long hair, is never extended to the house of mourning; and when a family is visited by the king of terrors, their feelings are so far respected, that they rosy violate this despotic edict, and allow their locks to grow.

NOTE