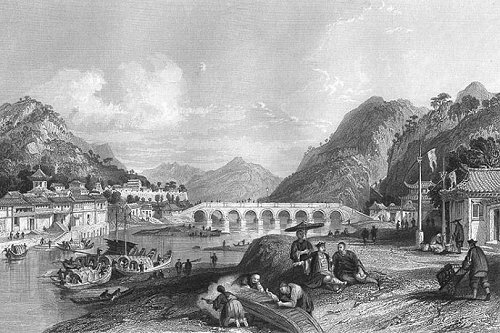

Few scenes in the whole winding water-way of the Kan-kiang present a more picturesque assemblage of objects than the vicinity of the great bridge of Yuk-shan. Here the granite ridges descend from their majestic elevation to human accessibility, and to human purposes also, leaving rocky ledges everywhere along the river-cliffs, where habitations are erected; and there earth may be deposited, or disintegration take place, sufficient to sustain vegetable life. On one bank a toll or custom-house is established, in front of which waves the imperial flag, one of the most decided badges of despotism in existence. The officer of customs is seated before the door, sheltered from the rays of a burning sun by a bamboo umbrella of considerable diameter, beneath the weight of which his slave is sinking; while the duty of examining each cargo, detecting violators of excise-law, and repairing of pit-pans for the service of his men, is proceeding with alacrity on all sides.

Tea, silk, cotton, are conveyed hither in country barges, and with the stream, from the fertile district north of the Melung mountains; but there is a superstitious reverence attached to the bridge of the "Nine Arches," which leads the Chinaman to fear a change of fortune, should he not change his junk when he arrives within view of this ancient monument.

Famous as is the structure that bestrides the flood at Yuk-shan, the roadway is but a few paces in width; the architect having only intended it for those who knew " to ride on a bay trotting-horse over four-inch'd bridges." No idea of terminal or lateral pressure ever entered the calm conception of the engineer; he calculated on the strength of the materials, perpendicularity of the piers, adhesive quality of the cement, and obedience of the emperor's subjects, who would not dare to drive a team of cattle, if they possessed any such useful concentration of animal power, along its narrow causeway. Fauy-tchoui, a celebrated hero of the days of old, constructed this bridge for the safe passage of his army; but, being a sorcerer and a soldier, he declared it to be unlucky to pass under it, in the same barge that arrived at its arches either from the lake, or from the fountain. Possibly the hero might have distrusted the stability of his structure, and been desirous of keeping off heavily-laden junks. However, some years after, a resolute character in the district, Ouan-tche, who conducted an extensive carrying-trade, determined to make experiment of the fact, but, before he entered the arches, repaired to a neighbouring temple, or hall of ancestors. Here he commenced calling on the shades of departed greatness, and bowing most reverently to the idols and pictures; his trackers at length becoming uneasy at his protracted absence, entered the hall in search of their master, where they 'beheld him enacting ko-tows with the utmost diligence, as if he had only then begun. After some delay, they ventured to approach, and signify that he had been perhaps longer engaged in worship than was beneficial, or probably intentional; but in vain-for the spell had bound him, and from that day to that day twelvemonth, Ouan-tche never ceased making ko-tows in the hall of ancestors at the bridge of Yuk-shan. Satisfied of his sin, on being released from enchantment, he acknowledged his fault, and immediately setting to work, built the long line of store-houses on the south bank of the river, which from that period has served as an entrepot for all goods in transit.