"Twelve miles from Peking, and at the point where the Pei-ho ceases to be navigable by junks or boats of burden, is situated Tong-chow-foo, a city of the second rank. It is surrounded by brick walls upwards of sixty feet in height, and possesses a dense population, apparently in a state of poverty, although, from the place being the port of Peking, an active trade is conducted. Hither the produce and manufacture of the southern provinces, as well as any foreign importations that elude the vigilance of Imperial illiberality at the sea-ports, are carried, and landed, and hence conveyed to the capital. In English history, the name of this populous, bustling, yet impoverished place, occurs; for it was here that Duke Ho, and President Muh, had that memorable interview with Lord Amherst, in which they explained to his excellency the nature and necessity of those genuflections and prostrations which he would be called upon to make when presented to the emperor.

It may possibly form a subject of regret that our ambassador returned without having accomplished any of the objects of his expensive mission; and it is known that Napoleon ridiculed his fastidiousness; but, judging from subsequent experience of Chinese cha Yaceei, it is more than probable that, had his lordship yielded a single point, where the honour and dignity of his country and sovereign were concerned, as "increase of appetite grows by what it feeds on," the Chinese would have grown more insolent in their demands and he would have left, with the additional chagrin of having paid homage, in the name of his royal master, to a Tartar potentate. Napoleon was not an emperor when he smiled at the squeamishness of the British ambassador; when the imperial diadem enwrapped his brow, he would not have suffered his representative to make an obeisance so humiliating, and in the name of France, before any monarch in the civilized World.

"A sufficient supply of wholesome food seems to be the influencing power, the spring of action, the end of industry, in every part of our globe; and the difference in the degrees of avidity with which mankind pursue it, is regulated by the degree of civilization and intelligence to which they have attained. It does not follow, that the acquisition of food is an object of less anxious attention in the educated countries of Europe, because they subdue the coarser appetites of our nature, and publicly exalt intellectual pursuits and refinements. Such nations have the same natural wants as their Eastern fellow-creatures; but, the very refinement which conceals them is also an auxiliary to the acquisition of a regular and satisfying supply. In China the voracity of the people obtrudes itself continually; every object of industry or occupation seems to have such a tendency to the appeasing of appetite, that it becomes rather a disgusting contemplation. The rich and elevated are decided epicures; the middle and lower classes as decided sensualists. The tastes of the one are scarcely limited by the extent of their revenues, the voracity of the other unrestricted by the most nauseous species of food.

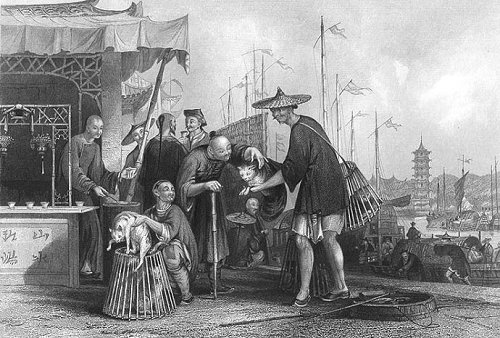

"Being the most omnivorous people in the world, there is not an animal or plant that can be procured by art and industry, and eaten without risk of life, that is not pressed into the service by these astronomers: the flesh of wild horses is highly prized, the larvae of the sphinx-moth, bears' paws, and the feet of other animals brought from Tartary, Cambodia, and Siam, are deemed delicious; and edible birds' nests are esteemed at the banquets of the mandarins, for which they are occasionally made into a soup. In the market Tong-chow, to which the stewards of the noble families of Peking repair to purchase viands for their lords, it is a good diversion to see the butchers, when they are carrying dogs' flesh to any place, or when they are leading five or six dogs to the slaughter-house: for, all the dogs in the street, drawn together by the cries of those going to be killed, or the smell of those already dead, fall upon the butchers, who are obliged to go always armed with a long staff, or great whip, to defend themselves from their attack, as also to keep their doors closed shut, that they may exercise their trade in safety. The salesmen enter the marketplace, or step from their junks upon shore, having baskets suspended at the extremities of a carrying-pole, in which are contained dogs, cats, rats, or birds, either tame or wild, generally alive--sea-slugs, and grubs found in the sugar-cane. The species of dog most in request is a small spaniel; the poor animals appear particularly dejected in their imprisonment, not even looking up in the hope of freedom; whilst the cats, on the contrary, maintain an incessant squalling, and seem never to despair of escaping, from a fate which otherwise must prove inevitable. To a foreigner, Christian or Turk, the sight is sufficiently trying, both regarding the dog as amongst the most faithful of inferior animals, and the cat as one of the most useful. In the ancient Chinese writings, cats are spoken of as a delicacy at table; but the species alluded to was found wild in Tartary, and brought thence into China, where they were regularly fed for the markets of the principal cities. As far as appearance is concerned, cats, when butchered, for they are not brought to market alive, are by no means disgusting. They are neatly prepared, slit down the breast, and hung in rows from the carrying-poles by skewers passed through their distended hind-legs.

"In the immediate vicinity of the wharfs, or horses' heads, the accustomed name for landing-places or jetties amongst the Chinese, at Tong-chow, are stalls where refreshments are sold to the boatmen and loungers; tea, however, is the universal beverage; and the vender, standing beneath a canopy of sail-cloth, made of the fibre of the bamboo, and supported by bamboo canes, invites all passers-by to taste the favourite refreshment. Cups, much inferior in capacity to those in general use amongst us, are laid with regularity along a marble counter, at the end of which stands a stove and boiler, where the tea is prepared and kept warm. The scene around presents an extraordinary instance of the universal application of the bamboo. Beside the tarpaulin supporters, table-frame, and trellis-work of the tea-vender's shop, the conical baskets in which the cats are brought to market, the pole from which they are suspended, the broad-leafed hat of the cat-merchant, the walking-stick of the buyer, the masts, sails, ropes, of the trading junks which lie close to the shore, as well as the frame-work and sail-cloths that sustain and form an awning, are all obtained or manufactured from this invaluable cane.

Tastes less fastidious would probably not repudiate the wild birds, eagles, storks, hawks, and owls, which are amongst the rarities arrayed by poulterers; although they are excluded from all European markets, with perhaps little reflection upon the grounds of that exclusion. But the popular fowl in China is the duck, in the rearing of which Chinese perseverance and animal instinct are conspicuous. In every province, the peasantry are familiar with the mode of hatching eggs by heat, either in an oven or a manure-heap. When the ducklings are able to be removed, they are put into boats, and carried away to the nearest mud bank or heap where shell-fish feed. Arrived at the scene of action, the conductor strikes on a gong, or blows a whistle, upon which signal his flock instantly paddle away to the feeding-ground, and commence a search for everything digestible. On the repetition of the signal, they paddle back again to their respective conveyances unerringly, although one hundred boats, and so many flocks, might be on the feeding ground at the same time. As the flock approaches, the conductor places a broad plank against the boat's side for the young waddlers to ascend; and the scene that takes place when the crowd reaches the plank is both interesting and ludicrous. It forms part of the conductor's duty to chastise the loiterers, but reward the most docile and active; this he does by giving the foremost of those that return some paddy, but the last a few taps of a bamboo; when, therefore, they reach the inclined plane, the efforts of all are redoubled, and the older and stronger actually waddle over the backs of the juniors into the boat, influenced evidently by a sense of rewards and punishments. This mode of feeding, however, is little calculated to produce fat or tender food; and when the ducks are dried, they present the appearance of skin strained over an anatomical prepation of that aquatic bird. "A man hawking about the streets of a town," says Mr. Lay, "with a bundle of dried ducks at his back, might be taken as a characteristic of the Chinese nation. The blood of the domestic fowl is spilled upon the ground, but that of the duck is preserved in a small vessel, that it may be moulded into a cake by the process of coagulation; it is then put into water, to displace a portion of the colour, and to enhance its good qualities. We see then that the Chinese are discriminating, even in the use of that inhibited article, blood: 'For blood, with the flesh thereof, which is the life thereof, ye shall not eat'."

NOTE