The limestone district of King-tan, being visited not only by passengers in traveling barges, but also by trading junks, presents more frequent examples of the deplorable despotism of this great empire than most other localities. The maxim may not be an unsound one, that provides as much and as constant occupation for a multitudinous people as possible, and performs everything by manual labour or animal power, where mechanism does not present competition; but even this political theory is insufficient to justify the cruelty exercised over the tribe of trackers. Descending from the mountains, where the soil denies support to the majority of those that first drew breath amidst their summits, a robust and hardy set of men undertake the toilsome life of trackers (tseen-foo). Half naked, and furnished with a description of gear, consisting of a breast-board, or sometimes a cushioned wooden bar, to the ends of which the ropes are attached, a number of men, regulated by the burden of the junk, is harnessed to the work of pulling against the stream.

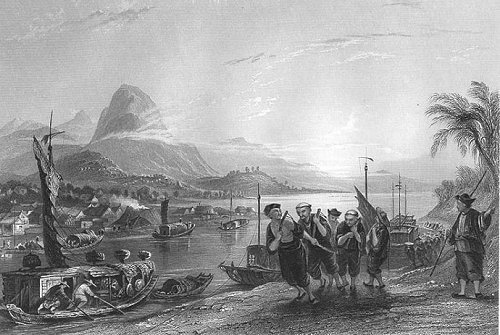

Their attitude and efforts are fully expressed in the illustration, where they appear not merely to give their muscular power, but their corporal weight, to strain the chief rope that is tied around the mast-head. When this laborious occupation is undertaken voluntarily, its followers are deserving of the compassion of the wealthy and the powerful; and those who are benefited by their efforts are bound to encourage, remunerate, and protect them. Such, however, does not appear to be the lot of the tracker. Engaged for sixteen successive hours, during which no space for refreshment is allowed, time being an object to his merciless employer, he is kept unflinchingly to his work by an overseer supplied with a long bamboo.

This humble application of human power is rendered still more humiliating from the cruelty and despotism exercised by government to obtain trackers, on any emergency. A Tartar corps is despatched to scour the country through which the imperial junks are about to pass, and press into the service all ages without distinction. It is in vain that parents plead the tender age of their offspring, or their own declining years-Tartar ears are ever closed against appeals of mercy; and father, husband, sons, are indiscriminately and violently enrolled in the service of the state. The revolting nature of the duty to those whom hard necessity has not previously compelled to adopt this peculiar mode of life, is such, that dependence cannot be placed upon many who have received the imperial summons, and desertion would be the immediate and inevitable consequence of notice. To anticipate this result, the impressed men are driven into an adjoining temple, or station-house, and there immured, sometimes for days, until the arrival of the junks, and of the trackers whom they are destined to succeed. A lictor now undertakes their management, and plies his long bamboo, emboldened by the confidence which a Tartar troop inspires. Trackers in the government-service undergo the most distressing fatigue; sometimes they have to wade through mire that comes up to their very arms, at others to swim across creeks and rivulets, and immediately after expose their naked and exhausted bodies to the painful influence of a burning sun. Resistance is met by stripes, or by the punishment of face-slapping;-obedience, by wages of one shilling a day, without any consideration of the time that will be occupied in the return of those ill-used beings to their families and homes.

The effects of this inhuman conscription, to which impressment of seamen in England bore some analogy, is often attended with the most lamentable consequences. Sudden transitions from heat to cold, and vice versa, induce fevers, which, in the destitute condition of the patient, generally prove fatal; and Europeans, during the course of a few days' journey, have seen many of these victims expire from hunger, fatigue, and the inhumanity of the lictors.

Much has been said about the trackers' song, and some travellers have likened it to our sailors' " ho-heave-ho'' or to our ploughman's whistle; but these are emblems of freedom, of hearts contented and at rest, and of a willing industry; while the tracker's song is a mournful sound, that summons each brother of the trade to alleviate the burden of his neighbour by pulling in due time. There is neither harmony nor cheerfulness in the poor Chinaman's chorus of Wo-to-hel-o, in which the saddest letter of the alphabet predominates.

Note