The poet's apostrophe to fallen Rome is so singularly applicable to the desolation prevalent at Nanking, that the traveller who shall have visited both cities, cannot refrain from instituting a comparison; for " her gates are desolate," and, " all her beauty is departed." "In the small portion," writes Mr. Davis, "which the inhabited part bears to the whole area of the ancient walls, Nanking has a strong resemblance to modern Rome; though its walls are not only much higher, but more extensive, being about twenty miles in circuit. The unpeopled areas of both these ancient cities are alike, in as far as they consist of hills, and remains of paved roads, and scattered cultivation, but the gigantic masses of ruin, which distinguish modern Rome, are wanting in Nanking since nothing in Chinese architecture is lasting, except the walls of their cities.

As I stood at Rome, on the Caelian Mount, the resemblance of its deserted hills (setting apart the black masses of ruin) to those of Nanking, struck me at once, bounded as they are, in both instances, by an old wall."

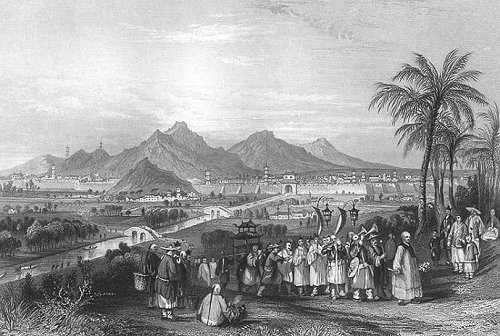

Nanking, the capital of Kiang-nan, situated in latitude 32° &' north, longitude 118° 47' east, within three miles of the Yang-tse-kiang river, and about 600 miles distant from both Peking and Canton, was formerly the metropolis of the empire, and one of the finest cities in the world. Chinese writers assert, that " if two horsemen were to set out in the morning at the same gate, and were to gallop round by a different way, they would not meet before night; " and its population, when Nanking was the Imperial residence, has been estimated, by the same authorities, at three millions. Several canals form an easy communication with the Yang-tse-kiang; and large barges, and Imperial luggage junks, navigate them with the most perfect facility. The famous pirate, or rather patriot, Cosinga, having sailed up the river, entered the canal, and laid siege to Nanking, it was deemed advisable, on his retirement, to block up the entrance of the latter, so as to obstruct the passage of all vessels of war. The example of the gallant conqueror of Formosa, however, was not lost upon the British; who, in the Ghiaese war of l840, pursued precisely a similar policy, penetrating also to the ramparts of Nanking.

The spacious enceinte of the walls is of an irregular outline, and varied by plain and mountain, the latter, like the castle-hill of Edinburgh, impending over the public ways. One third, at least, of the whole area, now lies desolate; the palaces, temples, observatories, and imperial sepulchres, having all been overthrown or demolished by the Tartars. When this city was the imperial seat, and the six great tribunals were held here equally with Peking, it was called Nanking, " the Court of the South; " but, upon the removal of the royal family, and the halls of justice, to Peking, ''the Court of the North," the emperor named it Kiang-ning. Pride, prejudice, and practice, however, have so successfully opposed imperial caprice, that the name of Nanking is still perseveringly retained by the Chinese. A city of the first class, Nanking is the residence of a great mandarin, (Tsong-tou,) a viceroy presiding over the two Keang provinces, to whom an appeal lies, in all important matters, from the tribunals of the East and West divisions. The fierce Tartars, whose ancestors spoiled Nanking of its splendour, and transferred the seat of empire to the Northern capital, still guard with jealousy the actions of the aboriginal people, in this, their ancient capital; and, a strong Tartar garrison, under the command of a general of their own nation, constantly occupies a sort of barrack or citadel, separated from the rest of the city by an embattled wall. The streets, in general, are narrow and inconvenient; the public buildings contemptible, with the exception of the city gates, which here, as well as in many of the principal cities, are remarkably fantastic and beautiful, and of the public monuments, erected by imperial command, to perpetuate the fame of a favourite.

When our King Charles once threatened to take the Court away from London, the citizens answered, that they should not much object, if he only left them the river Thames. The Tartar victors had but the monarch's wisdom, when they carried their emperor to Peking, leaving to the citizens of the old capital the navigable waters of the Yang-tse-kiang. Retaining their industry, which seems to have received a new impulse by the withdrawal of the vain, and idle, and dependent attaches of a regal residence, the Nanking manufacturers have brought their labours to the highest degree of excellence. The satins, plain and flowered, made here, are most esteemed at Peking, even those of Canton being postponed and sold at lower prices; the cotton cloth woven here, and bearing the name of the city, has long been admired in Europe; rice paper, and artificial flowers, formed from the pith of a leguminous plant called Tong'-fsao, constitute also a very important part of the prevailing manufactures. At Hoei-tcheou, in the province of Kiang-nan, the celebrated "Indian ink," so much prized in England, is manufactured; but it is sold for exportation principally at Nanking.

In this ancient city, learning also has long been seated, and a larger proportion of doctors, and great mandarins, and distinguished scholars, is sent hence to Peking and its colleges, than from any other city in the empire. Public libraries are numerous - the trade of a bookseller particularly respected-printing better understood than elsewhere is China, and the paper of Nanking is almost a miracle amongst national manufactures.

Peking is dependent upon her deserted sister, for many of the elegancies, and even some of the necessaries, of life. During the months of April and May, when fish is less abundant in the north, the Yang-tse-keang yields a most plentiful supply. These treasures of the deep being collected in great numbers, are packed in ice, put on board junks adapted to the purpose, and sent, by river and canal, to Peking, a distance of six hundred miles. When any are intended for the imperial family, relays of trackers, like our arrangements of post-horses before the introduction of railways, are in readiness; and this great distance is accomplished, by such clumsy machinery, in the amazingly short period of ten days and nights.