About twelve miles from the archipelago of Chusan, and on the left bank of the Ta-hea, or Kin river, stands the walled city of Ning-po, which Europeans formerly called Liam-po. It is the fourth city of the province of Tche-kiang, is itself of the first order, having four of the third under its jurisdiction, and enjoys the advantage of a good roadstead. Seated at the confluence of two rivers, the Ta-hea and Yao, its position is both agreeable and convenient; and the trade between this port and Japan has always been of an active character. A very level plain surrounds the site of Ning-po, extending to a distance of many miles on every side, and confined ultimately to the form of a vast oval basin, by lofty mountains, that rise abruptly and terminate the view. Many towns speckle the smooth surface of these fertile fields, on which also vast numbers of cattle are fed, and luxuriant crops of rice, cotton, and pulse are raised.

Nowhere in China is irrigation more advantageously or more skillfully adopted, than in the rich plain of Ning-po, the waters that descend from the encircling mountains being directed into sixty-six canals, all which, after contributing their services to the duty of fertilizing, discharge, their surplus into a main trunk that communicates with the Ta-hea. The amphitheatre of hills, the luxuriant vegetation of the well-watered plain, the occurrence of so many comfortable-looking towns, the brilliant sky, the wholesome and salubrious climate, and the great variety of trees, combine in the formation of a picture whose character is the most happy and agreeable. "The scenery about Ning-po," writes commander Bingham, " formed the prettiest landscape we had seen in China."

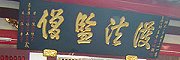

Its walls, extending rather more than five miles, are entirely of granite; and five gates afford admission within them. There are also two water-gates, these are mere arches in the walls, through which canals pass, each being protected by a portcullis. The public buildings are mean, and few in number, trade having for ages so completely absorbed the attention of the citizens, that the fine arts fell into oblivion. One lofty pagoda of brick, is the sole architectural boast of the place; and a bridge of boats over the Ta-hea, constructed about three centuries back, still retains its position. The streets are rather broader than those of Canton, and the shops better furnished, especially with japan-ware; but their width suffers an apparent diminution from the pent-houses which project beyond the shop-fronts. In the early years of the last century the English were permitted to trade here ; but the intrigues of the Portuguese and Russians, combined with the bigotry of the Chinese, deprived them of that valuable privilege, and restricted their merchants to the ports of Canton and Macao. To this advantage, however, our commerce is restored by the treaty signed after the conclusion of the opium war, and Ning-po for many years has participated more largely- in foreign trade, exchanging her silks, cottons, teas, and lacquered-ware, for the woolens and hardware of England, than any other of the free ports of the empire.

Upon the visit of Mr. Lindsay, in the ship Amherst, he found the inhabitants inclined to renew their friendly intercourse with the Ta-ying Kwo-jin (Englishmen), whom they had been taught by their government to designate as hak-kwae (black- demons), and hung-moon (red-bristles), and by other insulting and detracting epithets. The mandarins, however, had no authority to treat with Mr. Lindsay; and his mission proved as fruitless as those persons who were acquainted with the political condition of China had anticipated. During the continuation of the opium war the dastardly character of the Chinese, and the degraded state to which they are reduced, by the absolute quality of the despotism to which they submit, were conspicuously exhibited in their treatment of the shipwrecked crew of the Kite transport-ship. Having got possession of Mrs. Noble, widow of the master, they flogged her with a bamboo, put a chain round her neck, dragged her in this condition through the most public streets of several towns, and then put her into a criminal's cage, according to the infamous instructions of their laws. Captain Anstruther endured similar indignities, and many of the sailors were suffocated in a " black hole," where they were immured so long, that when released, the survivors appeared like so many skeletons in chains.

But retribution was not long delayed; that equilibrium, which is maintained by the laws of nature, finds a parallel in the balance sustained by the codes of justice and humanity. Captain Elliott in vain endeavoured to obtain the liberation of the prisoners; evasion and falsehood alone were employed by the Chinese in their negotiations. The following year, after the capture of Ching-hai with terrible slaughter, Rear-Admiral Sir W. Parker proceeded to the attack of Ning-po. The strength of his fleet, which consisted of the Modeste, Columbine, Cruiser, Bentinck, with the steamers Sesostris, Queen, Nemesis, and Phlegethon, alarmed the mandarins; and their fears were so much increased by intelligence of the fall of Ching-hai, that, when our troops landed, they found only a deserted city. Sir Thomas Herbert, at the head of the naval brigade, advanced to the gates, which were immediately forced, and entered the market-place without firing a single shot; the band of the 18th, meanwhile encouraging our men, and delighting the astonished Chinese, who clung to their homes, with the old Irish air of Garry Owen. Thus were the injuries of Mrs. Noble, Captain Anstruther, and the imprisoned seamen, gloriously avenged by the gallantry of their countrymen.

The other large towns, in the plain of Ning-po, offering no resistance, British superiority was acknowledged. Sir Henry Pottinger proceeded up the river, a distance of forty miles, to the city of Yuyaun, which the authorities had also abandoned; but shallow water, and the interruption of a stone bridge of six arches, prevented his further progress. Ning-po was rich in spoils; corn, silver, articles of the rarest manufacture, were carried away as trophies of the conquest of this ancient city, where more than half a million of inhabitants were located. The richest and most interesting of these emblems of victory is the "Great Bell," the finest specimen of refinement in taste and workmanship ever brought into Europe. It is composed of tin, copper, and silver, is five feet in height by three in diameter, and adorned with bands and panels enriched by reliefs and inscriptions. The figures are those of the Buddhist priesthood, whose origin is known to be Hindoo; and the inscriptions, according to the interpretation of that eminent Oriental scholar, Mr. Samuel Birch, of the British Museum, are in the Sanscrit character; they imply that the bell was cast for the temple of Shaou-ching, on the eighth moon of the nineteenth year of the reigning emperor, Taou-kwang, that is, in 1839. This gorgeous trophy, with its scalloped mouth, and graceful contour, resembling the Campanula Tremuloi'des, is now preserved in the library of Buckingham Palace, as a memento of the war with China.